The Star card from the original Rider-Waite deck, published 1909.

As a Tarot practitioner and artist who has created her own Tarot deck, I was drawn to the task of following the image of the seventeenth trump, the Star. Carl Jung distinguishes between free association and active imagination approaches to following an image. Free association takes one on a tangential journey, while active imagination circles around the image, always returning to the source, layering ideas and intuitive insights onto the image as one delves deeper into its meanings (Nichols 307). I have tried to use active imagination in this exploration, and when I have inevitably strayed into free association, I have tried to recognize my wandering and return to the image. My own approach, in this paper, most closely resembles an archetypal depth psychological one, although I also venture into religious and historical studies.

While seeking to define the symbols in the Star card, I began to understand Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lament over the “awful omniety in unity” because it is tempting to associate every goddess archetype with the card’s female figure that I call the Star Woman (Coleridge 100). I focus on the Star Woman as an archetype of transformation, a type of symbol that Jung described in “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious” as “ambiguous, full of half-glimpsed meanings, and in the last resort inexhaustible.” In this same section, Jung makes one of his only references to Tarot, “It also seems as if the set of pictures in the Tarot cards were distantly descended from the archetypes of transformation […]. The symbolic process is an experience in images and of images” (CW 9.1: 80-82). Despite the inexhaustible manifold meanings of the archetype of transformation, I shall attempt to place the Star Woman image in a context and assign her a role. Stars are universally considered guides, and generally, the soul, or anima, is personified as female. The Star Woman represents a female soul guide or psychopomp. She is not, however, a guide for the dead to the Underworld, but rather a guide for the living, maturing soul, one who mediates between the conscious and unconscious realms and assists in the individuation process. She is a guide for the soul’s Celestial Ascent.

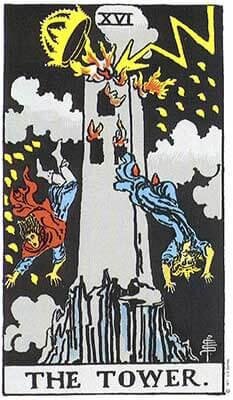

The Star card from the Cary Sheet, c. 1500

The Tarot trumps represent the hero’s journey as played by the zero trump, The Fool. The Fool progresses through the twenty-one trumps, in numerical order, in his initiation process. His journey resembles the three phases of the Neoplatonic dialectic emanatio—conversio—remeatio, or procession—conversion—re-ascent (Wind 125). In the Neoplatonic system, Mercury acts as the psychopomp for the subject’s re-ascent; in the Tarot system, rooted in the Gnostic and Hermetic traditions, the Star Woman acts as the psychopomp for the individual’s re-ascent. Christine Payne-Towler, a Tarot expert, believes that the Star reminds the soul of “our exalted origins and attraction to the path of return. An alternate title for this card is ‘Celestial Mandate’ in that it refers us back to our reason for being, our mission in this lifetime.” In this interpretation the Star connects an individual soul, his or her microcosm, with the universal macrocosm, inspiring new vision aimed upward to the heavens. The Celestial Ascent is a Hermetic tenet, as this quote from The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, a central Hermetic text, reveals, “From the highest to the lowest, everything rises by intermediate steps on the infinite ladder” (Campbell 49). With respect to alchemy, the Star initiates the ascendant move into albedo, the whitening stage, particularly with her water rituals emulating baptisma or ablutio, and her identification with the soul’s reunion with the body after the downfall of the Tower card, the sixteenth trump directly before the Star (Campbell 144, Banzhaf 103). Simultaneously, the Tarot journey can be compared to the psychological individuation process, with the Star Woman initiating the soul into a higher level of consciousness.

The Star Woman’s position and function in the Tarot cycle establish that she acts as the soul’s guide for the ascent described above. Cards three through twelve represent the Fool, or individual soul, living in his unconscious duality, progressing through various stages of growth and challenge. Death enters at card thirteen, dismantling and transforming the Fool, leading to card fourteen, Temperance, a reflection of the Star Woman. Temperance also pours water with two vessels, but from one vessel to another in a closed system. She is fully dressed and sporting wings, unlike the simple, nude Star. Temperance reassembles the broken soul after death, providing rest before the next stages of the Underworld journey through the Devil and destructive Tower.

Rider-Waite Tower card

After the cataclysmic Tower, the Fool encounters the Star Woman, a symbol of hope and renewal. Joseph Campbell describes the Star’s guiding function in the context of the hero’s journey, “After Purgatory comes Paradise; for the function of God’s chastisement is to prepare the soul for its Heaven-journey […]. The stars of this picture card […] conduct us to the next and topmost range of this Tarot Honors series, where the highest revelations appear of those ultimate spiritual forces” (21-22). The final stages of this mystical journey culminate in the celestial realm of the Moon, Sun, Judgment, and World cards, then circle back to the zero card, The Fool. It is at the Star stage that the Fool recognizes that he can join in a non-dual unity with the divine, and she guides his soul into the last stage of his journey. Inna Semetsky describes the enlightened vision of the Fool after his fall from the Tower, “in this light the Fool is able to see ‘The Star.’ This is the star of hope and healing which empowers our Fool with confidence, realization of talents, and self-esteem” (10). The soul perceives itself in the Star Woman figure and awakens to its potential; it can now progress forward on its path. Sallie Nichols paraphrases a Cabalistic saying in the context of her discussion of the Star card, “When you have found the beginning of the way, the star of your soul will show its light” (309). When the soul awakens, through the Star Woman’s agency, it is activated and begins to generate its own inspiration and vital energy. The Star Woman initially inspires, but then the soul travels on without her explicit guidance, although perhaps the Fool’s anima continues to reflect Star beauty back to him. Perhaps the Fool “in-spires” the Star, as in “breathing her in,” intaking her soul essence.

The Star card from the Jodorowsky-Camoin Tarot de Marseille deck. Marseilles is a style of Tarot originating c. 1500.

The imagery in the Star card further proves her role as psychopomp and connector. The main components in the Star card are river water, fiery stars, the earth, trees or flowers, birds or butterflies, and a nude woman thoughtfully engaged in a pouring ritual. This card brings together the four elements of air, water, fire, and earth in a harmonious, orderly manner for the first time in the Tarot cycle. Sallie Nichols proposes that the four elements in the Star card can represent Jung’s four functions of the human psyche moving toward integration (303). The Star Woman’s navel is located at the card’s midpoint, bisecting the conjunction of heaven and earth. She is at the center of the mandala as the axis mundi. This physical connection between two realms parallels the interpretation that the Star Woman connects soul and body, conscious and unconscious, and individual microcosm with world macrocosm. Further, she pours the water she collects from the river, which symbolizes the unconscious, back into the river from one vessel and onto the earth from the other vessel. In this way, she conjoins the watery and earthly elements with her actions. In addition, she may symbolize the feminine aspect of the male Fool, his anima that is hidden from him. Jung’s concept of the anima not only denotes an individual’s soul, but also the feminine inner personality of the male unconscious. Viewed from this perspective, she and the Fool join together in a mysterium coniunctionis, an alchemical union of opposites reminiscent of Hermaphrodite. In every way, the Star Woman unites dualities, a job that complements her role as psychopomp for the Fool, whose ultimate goal is to resolve dualities.

Let us now explore some of the archetypes that the Star Woman is not. The inexhaustible labyrinth of manifold meanings circles the Star Woman but also brushes against other archetypes that may seem like her twins yet turn out to be more like cousins: related, but not exactly identical. The first and most obvious relative is Hermes or Mercurius. They have some aspects in common, particularly sharing the role of guiding souls up and down, across boundaries, deeper into the inner world of the unconscious and then back out again to give back to the world in a renewed conscious state. Star Woman seems less concerned with ushering souls into the afterlife, which is Hermes’ main job, and more focused on aiding the soul in finding meaning and work in the world, i. e. the individuation process. Jung associates Shakti, the Hindu soul energy, with Mercurius in his section on “Rex and Regina” in Mysterium Coniunctionis, “This medium [Shakti] has the nature of Mercurius, that paradoxical being, whose one definable meaning is the unconscious” (CW 14: 534). The Star Woman does embody a paradox that seems to have something to do with the unconscious, and so the kinship between her and both Shakti and Mercurius is relevant. The Star card is often generally associated with Mercury. Richard Roberts, co-author of Tarot Revelations with Joseph Campbell, associates “Mercurius in his female guise” with the Star card (95). And Papus also aligns Mercury with this card astronomically, as do many other interpreters (173). Yet Hermes plays some roles that are discernibly different from Star Woman. He is a trickster, but she is straightforward and pure in her motives. He is a public messenger to multiple other parties, while she conveys private messages to the individual. Hermes is sometimes androgynous and/or transgender, but the Star Woman is clearly female. They share similarities but are not identical.

Even though the Star card is usually assigned to Aquarius in an astrological scheme, I disagree. Aquarius is a masculine, extroverted sign, unlike the pensive, introverted Star Woman. He provides water, rather than moving already-existing water from one plane to another, physically and symbolically, as the Star does. The Water Bearer is another archetype that is tempting to associate with the Star Woman, but again, she is neither carrying water nor delivering it but ritually pouring it from one plane to another. Perhaps she is playing with it, but she certainly is not providing it for another. Neither is she the Lady of the Lake, who guides Arthur on his quest but for her own motives and with much interacting in the plot, nor is the Star a simple water nymph or Rhine maiden. She is not a siren or a mermaid or any kind of temptress or femme fatale. These designations are too mundane for the Star Woman’s role.

While the Star Woman is not mundane, she is also not the Great Goddess or anima mundi. That position is too grand for her. She deals on the microcosmic level, inspiring the individual. She is a singular soul guide for an individual’s unconscious, rather than the collective unconscious of anima mundi. She is more virginal sister than mother. She is the anima. Jung explores an Eastern perspective on the unconscious in “Commentary on ‘The Secret of the Golden Flower,’” “I have defined the anima as a personification of the unconscious in general, and have taken it as a bridge to the unconscious, in other words, as a function of relationship to the unconscious. […] The text says that consciousness (that is, the personal consciousness) comes from the anima” (CW 13: 62). He continues to compare the Eastern and Western views of the unconscious, stating that “consciousness does originate in the unconscious.” As the anima, the Star Woman pours water from two vessels, which could symbolize the conscious and unconscious states of the soul. She serves a dual purpose, to awaken consciousness in the Fool, but through his unconscious function. And so she has double vessels and sometimes double trees in the background. As the one ushering in non-duality, ironically, she deals in twos.

The anima is often associated with Wisdom, especially personified as a royal woman. In the “Rex and Regina” section of Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung describes a sacred marriage between the Queen of Sheba, who symbolizes Wisdom, and a man’s soul; he states that through the queen’s guidance “the drama of his own soul, his individuation process, is played out” (CW 14: 543). This description corresponds well with the Star Woman’s anima role. Another example from the same essay references the Biblical King Solomon. Jung writes that the Rosarium reports Solomon as saying about his daughter: “This is my daughter, for whose sake men say that the Queen of the South came out of the east, like the rising dawn [Venus or “morning star”], in order to hear, understand, and behold the wisdom of Solomon […] she wears the royal crown of seven glittering stars” (CW 14: 542). Although the imagery correlates with the Star Woman, the patriarchal emphasis on the father as the dispenser of wisdom to a female receptacle does not.

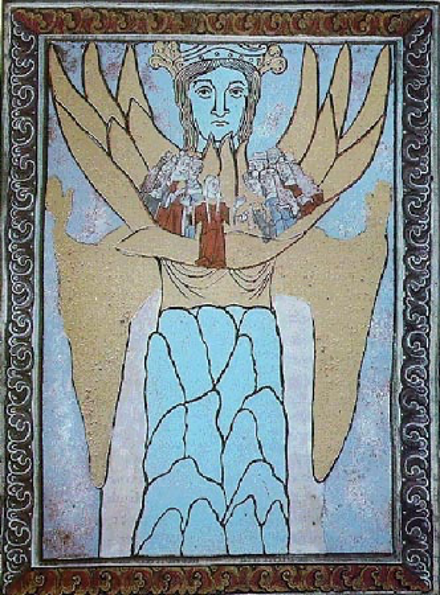

Painting of Sophia as Mother Church, by Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

In the Gnostic medieval Christian tradition, Sophia, another Wisdom persona, plays a more specific role that does not relate to the Star’s. First of all, in some stories, she descends to the Underworld, and Christ is the soul guide instead of her. Also, in Hildegard of Bingen’s iconography, she equates Sophia with the church as Mother Wisdom, painting her as a mermaid rising from the sea, embracing many people in her arms. Sophia is akin to the Great Mother here, unlike the Star Woman. Later Hildegard assigns Christian meanings to the celestial bodies that are quite different from the Tarot meanings: the sun is Christ; the moon is Mother Church; and the stars, “spreading out from themselves in the translucence of their glittering, signify the people of the diverse order of ecclesiastical religion” (Hildegard 72). So here the stars symbolize individual souls, which is actually closer to the Star’s and Tarot’s emphasis on the individual’s growth, but Sophia is aligned with the moon, which has a different meaning in the Tarot. However, the pairing of Wisdom with anima supports my interpretation of the Star Woman, who is a wise soul. A proper guide must be wise.

Stella Maris mosaic on St. Mary, Star of the Sea Church, San Pedro, CA

There is another central female figure from the Christian tradition who more closely resembles the Star Woman: Mary in her roles as “morning star” and Stella Maris. St. Bernard of Clairvaux was devoted to her, and, incidentally, he was also fascinated by the Bride in Song of Songs, another anima figure. Images of Stella Maris, meaning “Star of the Sea,” show Mary walking on water wearing a star halo as a guide for sailors. As the morning star, Mary also illuminates and guides the soul to God as the mediatrix. Bernard, as quoted by Dr. Mellifluus, implores people to “look at the star, call upon Mary” when they are tempted or lost. He entreats us to “turn not away thine eyes from the splendor of this guiding star, unless thou wish to be submerged by the storm!” An even more pertinent parallel with the Star Woman by Bernard: “[If] thou art beginning to sink into the bottomless gulf of sadness and to be swallowed in the abyss of despair, then think of Mary” because she will raise you up from the depths and into the celestial realm that can also be found here on earth (Mellifluus). Mary offers inspiration and hope, just as the Star Woman after the Tower’s brutal damage in the Tarot cycle. The “Ave Stella Maris” vespers hymn also reinforces her role as an illuminating guide in the lyrics, “Profer lumen caecis (Light on blindness pour)” and “Iter para tutum (Make our way secure)” (Gregorian Chant). Even though, unlike the Star Woman, Mary leads the soul specifically to Christ, both figures guide the soul on its Celestial Ascent toward divine union.

Gustave Doré’s illustration of Dante’s Paradiso XX1, 1-4.

Dante’s Beatrice is another classic anima guide from the medieval Christian tradition. When pagan Virgil must turn back in Purgatory, Beatrice replaces him as Dante’s guide, leading Dante on his Celestial Ascent through the ten spheres of Paradise to his final vision of the unfolding rose, an image reminiscent of a multi-pointed star. In Paradiso XXI, 1-4, Dante’s character expresses his soul’s joy in gazing on Beatrice, “Again mine eyes were fix’d on Beatrice; And with mine eyes, my soul that in her looks found all contentment.” Gustave Doré’s illustration of those lines shows Beatrice looking very much like the Star Woman, not kneeling on the earth, but in heaven standing on a cloud, surrounded by angels.

The very last word of each book of the Comedy is stella, implying that the journey circles outward and inward toward the celestial divine, with Beatrice acting as guide in the final phase. At the end, the Fool can arrive from trump twenty-one back to his zero position. The idealized female muse, the very image of Beauty, serves the man as his guide. Dante expresses his love for the departed woman Beatrice, but also his love for her soul, his soul, God’s soul, for the universal soul, and art. Depth psychologist James Hillman paired anima with eros, particularly in Renaissance thought. Dante’s work, although composed in the Middle Ages, ushered in the Renaissance approach, which Hillman believed was intent on soul-making, rooted in the imagination rather than the intellect, “hence its concentration upon the realm of anima.” “Preoccupation with love and beauty. . . are inherent in the movement of soul, the activity of anima, which seeks eros” (Hillman 211). And so it is okay to fall in love with these beautiful female soul guides; in fact, it is expected. One can love them as one loves all that is beautiful on the Celestial Ascent. One can love them in contrast to the shadowy Underworld. The Star Woman is pure in herself, but even more chaste when contrasted with the imagery in the Devil, Death, or Tower cards, her close neighbors. The darkness makes the light seem brighter. One cannot even see the stars until the dark falls.

Cover art for the film Lady in the Water, 2006

The Star Woman continues to reveal herself in contemporary art. Perhaps she will appear more often now that the Twin Towers have fallen. M. Night Shyamalan’s 2006 film Lady in the Water tells a myth about an anima figure, a water nymph called a “narf” who travels to our world, risking her life, to fulfill her role as a psychopomp. Her task is to appear to one man, Vick, and when he sees her, his soul will be filled with inspiration, and he will be able to complete an influential book that will later change world views. Vick’s response to seeing the narf, “My thoughts. Everything became clearer. The fears that were muddling my thoughts just went away. I can hear myself.” Vick seems to make direct contact with his soul through her inspiration.

The narf’s name is Story, but her role is more than allegorical; she also saves another character’s soul, Mr. Heep, awakening him from his (Underworld) grief over his murdered family to his purpose in the world. At the same time, Mr. Heep saves Story’s life. In the process, certain members of the apartment complex community discover that they also have important, though cryptic, roles to play in order to save Story’s life. In this contemporary myth, one female guide inspires and unites a community where each soul finds its unique gifts and role to play. The community engages in the cosmic dance to save Story, who is Beauty, Soul, Imagination, Art, just as humanity must act in concert to tend the world’s soul and imagination. Near the end of the film, Story affirms this interpretation when she says, “Man thinks they are each alone in this world. It is not true. You are all connected. One act can one day affect all.” The community’s mesocosm inspires us to think and feel for the macrocosm as well. Story played her role like the Star Woman, uniting, inspiring, giving hope and a universal perspective. She led the people toward the final phase of the Tarot cycle, unification and participation in the World card.

The cover art for the DVD reminds me of a dream image that Jung describes in Psychology and Alchemy: “The veiled woman uncovers her face. It shines like the sun. The solificatio is consummated on the person of the anima. The process would seem to correspond to the illuminatio, or enlightenment” (CW 12: 67-68). In the cover art, Story’s face radiates peace and hope amid tangled strands, spooky, dark corners, and a small male figure searching with a light. Like the Mona Lisa, she smiles a mystic secret. We are attracted to her mystery.

Author’s Star Tarot card, using the practice of SoulCollage®

The Star Woman symbolizes many qualities usually associated with female beauty, such as hope, inspiration, grace, and redemption. Acting as an archetype of transformation, she touches and awakens one’s soul through her anima. In my explorations of her function, I noticed the focus on the masculine soul as the subject. Particularly in the medieval Christian tradition and in Jung’s psychology, the muse or anima communicates with a male. Sallie Nichols addresses the lack of female perspective in a cursory sentence, “In a woman’s journey this figure [Star Woman], being of the same sex, would symbolize a shadow aspect of the personality” (301). Perhaps Nichols’ interpretation is valid, if we construe “shadow” strictly as a hidden aspect of the self, rather than engaging its murkier connotations. Yet the shadow seems the opposite of Star Woman’s imagery, position, and meaning, concealing light rather than illuminating, making something more secret rather than finally revealing it. Star Woman as shadow leaves the female subject unsatisfied, even cheated out of the full experience of her anima. Where are the females guiding other females? Where are the female voices? Must everything fit into the structure of duality and the joining of opposites? Apparently, I felt that the answer should be no when I created my Star card since I broke with tradition and included a Star Man along with my Star Woman. But I do not feel that an animus guides my soul. Without discarding the masculine, I still know that an anima figure is my Star Woman as well. If there is somewhere an image of a sacred marriage between a goddess and a human woman, perhaps the Star Woman’s soul would be complete.

Works Cited

Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy, edited by Charles W. Eliot. Harvard Classics, 1914,

www.bartleby.com/20/321.html. Accessed 7 Apr. 2009.

Banzhaf, Hajo. The Crowley Tarot: The Handbook to the Cards by Aleister Crowly and Lady

Frieda Harris, translated by Christine M. Grimm, U. S. Games Systems, 1995.

Campbell, Joseph and Richard Roberts. Tarot Revelations. Vernal Equinox, 1987.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Anima Poetæ: From the Unpublished Notebooks of Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, edited by Ernest Hartley Coleridge, London, William Heinemann, 1895.

Doré, Gustave. The Doré Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy. New York: Dover, 1976.

Gregorian Chant Lyrics. ChantCD.com, 2008. www.chantcd.com/lyrics/hail_star_sea.htm.

Accessed 1 Apr. 2009.

Hildegard of Bingen. Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen, edited by Matthew Fox, Bear and

Co., 1985.

Hillman, James. Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row, 1975.

Jung, C. G. “Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious,” translated by R. F. C. Hull. The

Collected Works of C. G. Jung. Vol. 9.1. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton UP, 1980, pp. 37-38.

---. “Commentary on ‘Secret of the Golden Flower,’” translated by R. F. C. Hull. The Collected

Works of C. G. Jung. Vol. 13. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton UP, 1983, p. 42.

---. Psychology and Alchemy, translated by R. F. C. Hull. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung.

Vol. 12. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton UP, 1993, p. 57.

---. Mysterium Coniunctionis, translated by R. F. C. Hull. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung.

Vol. 14. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton UP, 1989, pp. 377-78.

Lady in the Water. Dir. M. Night. Shyamalan. Perf. Paul Giamatti, Bryce Dallas Howard. Warner

Bros., 2006.

Mellifluus, Doctor. “On St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the Last of the Fathers.” The Holy See, 24 May

1953, www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_24051953_doctor-mellifluus_en.html. Accessed 2 Apr. 2009.

Nichols, Sallie. Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey. Samuel Weiser, 1980.

Papus (Gérard Encausse). The Tarot of the Bohemians, translated by A. P. Morton. 1892.

www.sacred-texts.com/tarot/tob/index.htm. Accessed 2 Apr. 2009.

Payne-Towler, Christine. “The Major Arcana Cards.” Tarot University. 11. Jan. 2006,

www.noreah.typepad.com/tarot_arkletters/2005/05/the_major_arcan.html. Accessed 13

Jan. 2009.

Semetsky, Inna. “The Phenomenolgy of Tarot, or: The Further Adventures of a Postmodern

Fool.” Trickster's Way, vol. 4, no. 1, article 3, 2005.

Wind, Edgar. Pagan Mysteries of the Renaissance: An Exploration of Philosophical and

Mystical Sources of Iconography in Renaissance Art. W. W. Norton, 1968.

Works Consulted

Anonymous. Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism, translated by

Robert A. Powell. Amity House, 1985.

Arrien, Angeles. The Tarot Handbook: Practical Applications of Ancient Visual Symbols.

Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1997.

Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard of Clairvaux: Selected Works, edited by Emilie Griffin,

translated by Gillian R. Evans, HarperSanFrancisco, 1987.

Cavendish, Richard. The Tarot. Harper and Row, 1975.

Crowley, Aleister. The Book of Thoth: A Short Essay on the Tarot of the Egyptians. Samuel

Weiser, 1985.

Davidson, Leah. “Foresight and Insight: The Art of the Ancient Tarot.” Journal of the American

Academy of Psychoanalysis, vol. 29, no. 3, 2001, pp. 491-501.

https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.29.3.491.17297

Eliade, Mircae. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, translated by Willard R. Trask.

Bollingen Series LXXVI. Princeton UP, 1992.

Evarts, Arrah B. “Color Symbolism.” Psychoanalytic Review, vol. 6, no. 2, 1919, pp. 124-157.

Frost, Seena B. “Waterbearer: Archetype of the Aquarian Age.” KaleidoSoul.

https://kaleidosoul.com/waterbearer.html. Accessed 14 Aug. 2025.

Gettings, Fred. Fate and Prediction: An Historical Compendium of Astrology, Palmistry and

Tarot. Exeter, 1980.

Lansing, Richard H. “Dante Alighieri.” World Book Online Reference Center, 2009.

Leeming, David. The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford UP, 20005.

Littleton, C. Scott, ed. Mythology: The Illustrated Anthology of World Myth and Storytelling.

Duncan Baird, 2002.

McLean, Adam. Alchemy. 2008. www.alchemywebsite.com/rosarium.html. Accessed 7 Feb.

2009.

“Our Lady, Star of the Sea.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 1 Apr. 2009

Semetsky, Inna. “Signs in Action: Tarot as a Self-Organized System.” Cybernetics & Human

Knowing, vol. 8, no. 1-2, 2001, pp. 111-132.

Toland, Diane. Inner Pathways to the Divine: Exploring your Spiritual Self through the Tarot’s

Major Mentors. Sunshine Press, 2001.

Waite, Arthur Edward. The Pictorial Key to the Tarot: Being Fragments of a Secret Tradition

Under the Veil of Divination. U. S. Games Systems, 2000.

Wanless, James. Voyager Tarot: Guidebook for the Journey. Fair Winds Press, 1998.